Sredni Vashtar

"Sredni Vashtar avanzava,

I suoi pensieri erano rossi e i suoi denti bianchi.

I suoi nemici imploravano la pace, ma egli portava loro la morte.

Sredni Vashtar il Bellissimo."

I suoi pensieri erano rossi e i suoi denti bianchi.

I suoi nemici imploravano la pace, ma egli portava loro la morte.

Sredni Vashtar il Bellissimo."

Saki, "Sredni Vashtar"

Se avremo inventato degli dei, e sappiamo di averlo fatto, con quale faccia sorpresa contempleremo il volto vero di Dio?

Che accadrà, nel giorno del giudizio, a chi ha fortemente voluto liberarsi dal male e dai propri carnefici invocando un dio inventato, eletto tra i simboli che fin dalla nascita ogni uomo può scegliere tra quelli che si trova via via accanto?

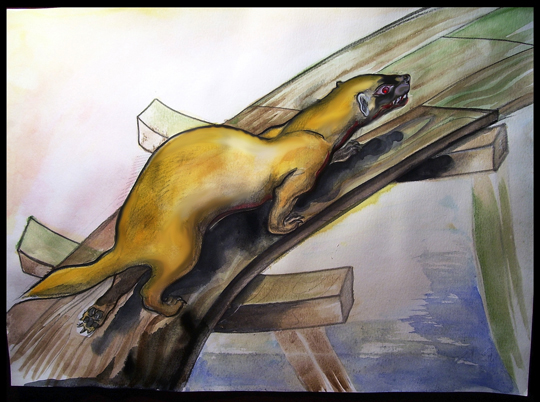

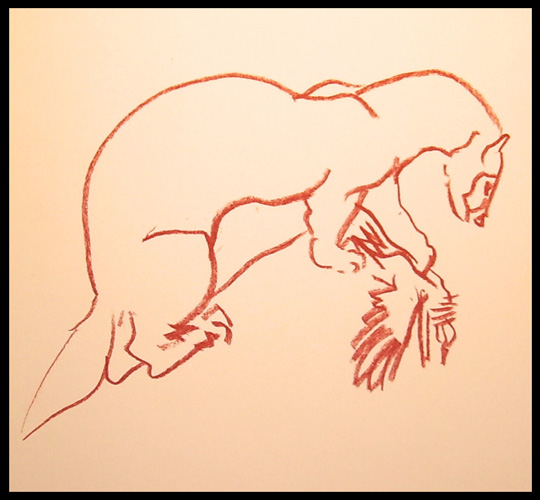

Anch'io ho inventato molti dei, e li ho nominati e invocati per poter innocentemente chieder loro che compissero per me le azioni più orribili, il lavoro sporco che non potevo richiedere alla divinità ufficiale. E molto mi sarebbe piaciuto che una di quelle deità fosse questo furetto. Veramente fantastico, perturbante e liberatorio sarebbe qualora una divinità inventata ci liberasse dal male dopo che gliene abbiamo fatto richiesta, e pazzamente l'abbiamo sperato e creduto.

Quante volte mi è accaduto questo, però nessuno dei miei bellissimi idoli mi ha mai liberato, senza poi, andandosene, liberarsi anche di me.

Che accadrà, nel giorno del giudizio, a chi ha fortemente voluto liberarsi dal male e dai propri carnefici invocando un dio inventato, eletto tra i simboli che fin dalla nascita ogni uomo può scegliere tra quelli che si trova via via accanto?

Anch'io ho inventato molti dei, e li ho nominati e invocati per poter innocentemente chieder loro che compissero per me le azioni più orribili, il lavoro sporco che non potevo richiedere alla divinità ufficiale. E molto mi sarebbe piaciuto che una di quelle deità fosse questo furetto. Veramente fantastico, perturbante e liberatorio sarebbe qualora una divinità inventata ci liberasse dal male dopo che gliene abbiamo fatto richiesta, e pazzamente l'abbiamo sperato e creduto.

Quante volte mi è accaduto questo, però nessuno dei miei bellissimi idoli mi ha mai liberato, senza poi, andandosene, liberarsi anche di me.

Sredni Vashtar

Conradin aveva dieci anni, e il dottore aveva emesso la sua opinione professionale affermando che il ragazzo non ne avrebbe vissuti altri cinque. Il dottore era un tipo untuoso ed effeminato e la sua opinione poco contava, ma era appoggiata dalla Sig.ra De Ropp, che invece contava più di ogni altra cosa. Mrs De Ropp era la cugina e guardiana di Conradin, e ai suoi occhi rappresentava quei tre quinti del mondo che erano inevitabili, spiacevoli e reali; i rimanenti due quinti, in perpetuo antagonismo con i primi, erano riuniti in se stesso e nella propria immaginazione. Conradin supponeva che un giorno o l’altro avrebbe ceduto sotto la terribile pressione delle necessità, come la malattia e le indulgenti restrizioni e la prolungata depressione. Senza la propria immaginazione, cresciuta a dismisura sotto la spinta della solitudine, sarebbe crollato già da lungo tempo.

Mrs De Ropp non avrebbe mai, nei suoi momenti più onesti, confessato a se stessa che Conradin non le piaceva, benché fosse in qualche modo consapevole che reprimere e frustrare le sue iniziative "per il suo bene" era un compito che non trovava poi così sgradevole. Conradin la odiava con una disperata sincerità che era perfettamente in grado di mascherare. Quei pochi piaceri che riusciva ad inventarsi guadagnavano un valore aggiuntivo dal fatto che sarebbero dispiaciuti al suo guardiano; ella era esclusa dal regno della sua immaginazione, era un essere indistinto che non poteva entrarvi.

Nel giardino desolato, sorvegliato da un gran numero di finestre pronte ad aprirsi con un messaggio di non fare questo o quello, o di ricordarsi di prendere le medicine, non trovava alcuna attrattiva. I pochi alberi da frutto erano tenuti gelosamente fuori dalla sua portata, come fossero rari campioni della propria specie fioriti in un’arida desolazione; sarebbe stato difficile trovare un fruttivendolo che avesse offerto dieci scellini per la loro intera produzione annuale. Tuttavia, in un angolo trascurato, quasi nascosto da un gruppo di squallidi arbusti, vi era un capanno per gli attrezzi in disuso di rispettabili proporzioni, e tra le sue pareti Conradin aveva trovato un paradiso, qualcosa a metà strada tra una sala giochi e una cattedrale. Egli lo aveva abitato con una legione di amici immaginari partoriti in parte da frammenti di storia, in parte dalla propria fantasia, e anche con due compagni fatti di carne e sangue. In un angolo viveva una spennacchiata gallina di Houdan su cui il ragazzo riversava tutto il suo affetto, che d’altra parte non trovava altra via di uscita. Più indietro, seminascosta dall’oscurità si trovava una grande gabbia, divisa in due compartimenti, uno dei quali sprangato da una fitta rete di barre di ferro. Era la dimora di un grosso furetto che gli era stato dato di contrabbando, completo di gabbia e di tutto il resto, da un amichevole garzone di macelleria in cambio di una piccola riserva di argento a lungo tenuta segreta. Conradin era terribilmente spaventato dalla bestia sgusciante e dai denti aguzzi, che però rappresentava il suo tesoro più prezioso. La sua presenza nel rifugio era una gioia segreta ed eccitante, da nascondere scrupolosamente alla Donna, come egli chiamava privatamente la cugina. Finché un giorno, il Cielo sa come, non inventò un nome meraviglioso per l’animale, che da quel momento crebbe nella sua considerazione diventando un dio e una religione. La Donna praticava la religione una volta la settimana recandosi in una chiesa vicina, e portava Conradin con sè, ma per lui la liturgia in chiesa rappresentava nient’altro che un rito alieno e senza senso. Ogni giovedì, nell’indistinto silenzio stantio del capanno, egli stava adorante, seguendo un mistico ed elaborato cerimoniale, accanto alla gabbia di legno in cui abitava Sredni Vashtar, il grande furetto. Fiori rossi di stagione e bacche scarlatte d’inverno venivano portati al suo cospetto, dato ch’egli era un dio che stava dalla parte più selvaggia e passionale delle cose, in opposizione alla religione della Donna, che, per quanto Conradin poteva constatare, andava per lunghe miglia nella direzione contraria. E in occasione delle grandi festività, della noce moscata in polvere, rigorosamente rubata, veniva sparsa di fronte alla sua gabbia. Queste occasioni erano irregolari, e servivano principalmente per celebrare qualche evento temporaneo. Una volta, in cui Mrs. De Ropp soffrì di un acuto mal di denti per tre giorni, Conradin festeggiò per tutti e tre i giorni, e quasi si persuase che Sredni Vashtar fosse stato personalmente responsabile del malanno. Se la malattia fosse durata per un solo altro giorno la scorta di noce moscata si sarebbe esaurita.

La gallina di Houdan non veniva mai inclusa nel culto di Sredni Vashtar. Conradin aveva da tempo stabilito che fosse una Anabattista. Egli non pretendeva di sapere esattamente cosa fosse un Anabattista, ma privatamente sperava che fosse una persona audace e non molto rispettabile. Mrs De Ropp rappresentava il riferimento sui cui egli basava, e detestava, tutta la rispettabilità.

La frequentazione assidua del capanno degli attrezzi da parte di Conradin non mancò di attirare l’attenzione del suo guardiano. "Non è bene che sprechi tutte quelle ore là dentro, con ogni tipo di tempo", decise senza indugi, e un mattino a colazione annunciò che la gallina di Houdan era stata rimossa e venduta la sera precedente. I suoi occhi miopi sbirciavano Conradin, aspettandosi una esplosione di rabbia e disperazione, che ella era pronta a reprimere con una sfilza di virtuosi precetti e ragionamenti. Ma Conradin non disse nulla: non c’era niente da dire. Forse qualcosa trasparì dal suo volto pallido facendole provare un momentaneo disagio, dato che nel pomeriggio il tè fu accompagnato dal pane tostato, una prelibatezza che usualmente ella proibiva per il bene di lui; e anche perché il prepararlo "recava fastidio", una offesa mortale agli occhi della classe media femminile.

"Pensavo che il pane tostato ti piacesse", esclamò, con un’aria irritata, osservando che egli non l’aveva toccato.

"A volte." rispose Conradin.

Quella sera, nella capanna, vi fu una novità nel rituale di adorazione della divinità. Conradin usava recitare delle preghiere, ma questa volta formulò anche una richiesta.

"Fai una cosa per me, Sredni Vashtar."

La cosa non era meglio specificata. Egli supponeva che Sredni Vashtar già lo sapesse, essendo un dio. Poi, guardando l’angolo vuoto, proruppe in un singhiozzo e se ne tornò nel mondo che odiava.

E ogni notte, nella gradita oscurità della sua camera, ed ogni sera, nella luce del crepuscolo, nel capanno si alzava l’amara litania di Conradin:"Fai una cosa per me, Sredni Vashtar."

Mrs De Ropp, notando che le visite al capanno non diminuivano, un giorno effettuò un nuovo giro di ispezione. "Cosa tieni in quella gabbia sprangata?" chiese. "Credo proprio che siano dei maialini di Guinea, farò una bella pulizia."

Conradin serrò forte le labbra, ma la Donna ispezionò con cura la sua camera, finché non trovò la chiave accuratemente nascosta, e quindi marciò risoluta verso il capanno per completare la sua scoperta. Faceva freddo quel pomeriggio, e a Conradin era stato proibito di uscire di casa. Si sistemò presso la lontana finestra della sala da pranzo, da dove la porta del capanno poteva appena essere scorta, oltre l’angolo del boschetto. Vide la Donna entrare e si immaginò mentre apriva la porta della sacra gabbia e sbirciava all’interno con i suoi occhi miopi il pagliericcio su cui giaceva il suo dio. Forse avrebbe rovistato la paglia nella sua goffa impazienza. E Conradin, ferventemente espirò la sua preghiera, per l’ultima volta. Ma egli fu consapevole, mentre pregava, di non crederci veramente. Seppe che la Donna sarebbe uscita con quel sorriso contratto stampato sulla faccia, che egli odiava così tanto, e che in un’ora o due il giardiniere avrebbe portato via il suo dio meraviglioso, ora non più dio, ma normale furetto marrone rinchiuso in una gabbia. E seppe che la Donna avrebbe trionfato per sempre, come trionfava ora, e che egli si sarebbe ammalato sempre di più sotto l’influsso della sua vessatoria saggezza superiore, finché un giorno non si sarebbe potuto fare più nulla per lui e la previsione del dottore si sarebbe avverata. E immerso nell’acuto dolore e nella miseria della sua frustrazione, iniziò a recitare fieramente e a voce alta l’inno del suo idolo minacciato:

Sredni Vashtar avanzava,

I suoi pensieri erano rossi e i suoi denti bianchi.

I suoi nemici imploravano la pace, ma egli portava loro la morte.

Sredni Vashtar il Meraviglioso.

Poi, improvvisamente interruppe il suo canto, e si avvicinò al pannello della finestra. La porta del capanno era ancora parzialmente aperta come era stata lasciata, e i minuti passavano. Erano minuti lunghi, ma ciononostante passarono. Vide gli storni correre e svolazzare nel prato; li contò e li ricontò senza mai perdere di vista la porta ondeggiante. Una cameriera dai lineamenti acidi entrò a preparare il tavolo per il té, ma Conradin non si muoveva, e aspettava, e guardava. La speranza era entrata nel suo cuore, e il bagliore del trionfo iniziava a lampeggiare nei suoi occhi che avevano fin lì conosciuto solo l’appassionata pazienza della frustrazione. Nascosto nel respiro, e con una furtiva esultanza, di nuovo iniziò il peana di vittoria e devastazione. Ma questa volta la sua attesa fu ricompensata: dalla porta sgusciò fuori una lunga bestia giallo-marroncina, con gli occhi fissi nella luce del giorno evanescente, e con macchie scure e umide tutto intorno alle mandibole e lungo la gola. Conradin cadde in ginocchio. Il grande furetto scivolò verso una pozza sul margine del giardino, bevve per un momento, quindi attraversò un ponticello e si perse alla vista nei cespugli. Questo fu il passaggio di Sredni Vashtar.

"Il té è pronto," disse la cameriera; " dov’è la signora?"

" E’ andata nel capanno, da un po’", disse Conradin. E mentre la cameriera andava a chiamare la signora per il té, Conradin afferrò una forchetta dalla cassettiera e si apprestò a tostare un pezzo di pane. E durante la tostatura e mentre imburrava abbondantemente il pane e lo gustava con dolce lentezza, Conradin ascoltava i rumori e gli intervalli che venivano in rapidi spasmi da oltre la porta della sala da pranzo. L’urlo stridulo e smisurato della cameriera, il coro in risposta di esclamazioni meravigliate dalla zona cucine, i passi affrettati e le concitate grida di aiuto e infine, dopo una pausa, i singhiozzi impauriti e i passi irregolari di quanti trasportavano un pesante fardello all’interno della casa.

"Chi lo riferirà a quel povero bambino? Io non ce la faccio!" esclamò una voce acuta. E mentre essi discutevano la cosa tra di loro, Conradin si preparava un altro pezzo di pane tostato.

Traduzione a cura di Alberto Dalla Fontana

Sredni Vashtar

Conradin was ten years old, and the doctor had pronounced his professional opinion that the boy would not live another five years. The doctor was silky and effete, and counted for little, but his opinion was endorsed by Mrs. De Ropp, who counted for nearly everything. Mrs. De Ropp was Conradin's cousin and guardian, and in his eyes she represented those three-fifths of the world that are necessary and disagreeable and real; the other two-fifths, in perpetual antagonism to the foregoing, were summed up in himself and his imagination. One of these days Conradin supposed he would succumb to the mastering pressure of wearisome necessary things---such as illnesses and coddling restrictions and drawn-out dulness. Without his imagination, which was rampant under the spur of loneliness, he would have succumbed long ago.

Mrs. De Ropp would never, in her honestest moments, have confessed to herself that she disliked Conradin, though she might have been dimly aware that thwarting him ``for his good'' was a duty which she did not find particularly irksome. Conradin hated her with a desperate sincerity which he was perfectly able to mask. Such few pleasures as he could contrive for himself gained an added relish from the likelihood that they would be displeasing to his guardian, and from the realm of his imagination she was locked out---an unclean thing, which should find no entrance.

In the dull, cheerless garden, overlooked by so many windows that were ready to open with a message not to do this or that, or a reminder that medicines were due, he found little attraction. The few fruit-trees that it contained were set jealously apart from his plucking, as though they were rare specimens of their kind blooming in an arid waste; it would probably have been difficult to find a market-gardener who would have offered ten shillings for their entire yearly produce. In a forgotten corner, however, almost hidden behind a dismal shrubbery, was a disused tool-shed of respectable proportions, and within its walls Conradin found a haven, something that took on the varying aspects of a playroom and a cathedral. He had peopled it with a legion of familiar phantoms, evoked partly from fragments of history and partly from his own brain, but it also boasted two inmates of flesh and blood. In one corner lived a ragged-plumaged Houdan hen, on which the boy lavished an affection that had scarcely another outlet. Further back in the gloom stood a large hutch, divided into two compartments, one of which was fronted with close iron bars. This was the abode of a large polecat-ferret, which a friendly butcher-boy had once smuggled, cage and all, into its present quarters, in exchange for a long-secreted hoard of small silver. Conradin was dreadfully afraid of the lithe, sharp-fanged beast, but it was his most treasured possession. Its very presence in the tool-shed was a secret and fearful joy, to be kept scrupulously from the knowledge of the Woman, as he privately dubbed his cousin. And one day, out of Heaven knows what material, he spun the beast a wonderful name, and from that moment it grew into a god and a religion. The Woman indulged in religion once a week at a church near by, and took Conradin with her, but to him the church service was an alien rite in the House of Rimmon. Every Thursday, in the dim and musty silence of the tool-shed, he worshipped with mystic and elaborate ceremonial before the wooden hutch where dwelt Sredni Vashtar, the great ferret. Red flowers in their season and scarlet berries in the winter-time were offered at his shrine, for he was a god who laid some special stress on the fierce impatient side of things, as opposed to the Woman's religion, which, as far as Conradin could observe, went to great lengths in the contrary direction. And on great festivals powdered nutmeg was strewn in front of his hutch, an important feature of the offering being that the nutmeg had to be stolen. These festivals were of irregular occurrence, and were chiefly appointed to celebrate some passing event. On one occasion, when Mrs. De Ropp suffered from acute toothache for three days, Conradin kept up the festival during the entire three days, and almost succeeded in persuading himself that Sredni Vashtar was personally responsible for the toothache. If the malady had lasted for another day the supply of nutmeg would have given out.

The Houdan hen was never drawn into the cult of Sredni Vashtar. Conradin had long ago settled that she was an Anabaptist. He did not pretend to have the remotest knowledge as to what an Anabaptist was, but he privately hoped that it was dashing and not very respectable. Mrs. De Ropp was the ground plan on which he based and detested all respectability.

After a while Conradin's absorption in the tool-shed began to attract the notice of his guardian. ``It is not good for him to be pottering down there in all weathers,'' she promptly decided, and at breakfast one morning she announced that the Houdan hen had been sold and taken away overnight. With her short-sighted eyes she peered at Conradin, waiting for an outbreak of rage and sorrow, which she was ready to rebuke with a flow of excellent precepts and reasoning. But Conradin said nothing: there was nothing to be said. Something perhaps in his white set face gave her a momentary qualm, for at tea that afternoon there was toast on the table, a delicacy which she usually banned on the ground that it was bad for him; also because the making of it ``gave trouble,'' a deadly offence in the middle-class feminine eye.

``I thought you liked toast,'' she exclaimed, with an injured air, observing that he did not touch it.

``Sometimes,'' said Conradin.

In the shed that evening there was an innovation in the worship of the hutch-god. Conradin had been wont to chant his praises, tonight be asked a boon.

``Do one thing for me, Sredni Vashtar.''

The thing was not specified. As Sredni Vashtar was a god he must be supposed to know. And choking back a sob as he looked at that other empty comer, Conradin went back to the world he so hated.

And every night, in the welcome darkness of his bedroom, and every evening in the dusk of the tool-shed, Conradin's bitter litany went up: ``Do one thing for me, Sredni Vashtar.''

Mrs. De Ropp noticed that the visits to the shed did not cease, and one day she made a further journey of inspection.

``What are you keeping in that locked hutch?'' she asked. ``I believe it's guinea-pigs. I'll have them all cleared away.''

Conradin shut his lips tight, but the Woman ransacked his bedroom till she found the carefully hidden key, and forthwith marched down to the shed to complete her discovery. It was a cold afternoon, and Conradin had been bidden to keep to the house. From the furthest window of the dining-room the door of the shed could just be seen beyond the corner of the shrubbery, and there Conradin stationed himself. He saw the Woman enter, and then be imagined her opening the door of the sacred hutch and peering down with her short-sighted eyes into the thick straw bed where his god lay hidden. Perhaps she would prod at the straw in her clumsy impatience. And Conradin fervently breathed his prayer for the last time. But he knew as he prayed that he did not believe. He knew that the Woman would come out presently with that pursed smile he loathed so well on her face, and that in an hour or two the gardener would carry away his wonderful god, a god no longer, but a simple brown ferret in a hutch. And he knew that the Woman would triumph always as she triumphed now, and that he would grow ever more sickly under her pestering and domineering and superior wisdom, till one day nothing would matter much more with him, and the doctor would be proved right. And in the sting and misery of his defeat, he began to chant loudly and defiantly the hymn of his threatened idol:

Sredni Vashtar went forth,

His thoughts were red thoughts and his teeth were white.

His enemies called for peace, but he brought them death.

Sredni Vashtar the Beautiful.

And then of a sudden he stopped his chanting and drew closer to the window-pane. The door of the shed still stood ajar as it had been left, and the minutes were slipping by. They were long minutes, but they slipped by nevertheless. He watched the starlings running and flying in little parties across the lawn; he counted them over and over again, with one eye always on that swinging door. A sour-faced maid came in to lay the table for tea, and still Conradin stood and waited and watched. Hope had crept by inches into his heart, and now a look of triumph began to blaze in his eyes that had only known the wistful patience of defeat. Under his breath, with a furtive exultation, he began once again the pæan of victory and devastation. And presently his eyes were rewarded: out through that doorway came a long, low, yellow-and-brown beast, with eyes a-blink at the waning daylight, and dark wet stains around the fur of jaws and throat. Conradin dropped on his knees. The great polecat-ferret made its way down to a small brook at the foot of the garden, drank for a moment, then crossed a little plank bridge and was lost to sight in the bushes. Such was the passing of Sredni Vashtar.

``Tea is ready,'' said the sour-faced maid; ``where is the mistress?'' ``She went down to the shed some time ago,'' said Conradin. And while the maid went to summon her mistress to tea, Conradin fished a toasting-fork out of the sideboard drawer and proceeded to toast himself a piece of bread. And during the toasting of it and the buttering of it with much butter and the slow enjoyment of eating it, Conradin listened to the noises and silences which fell in quick spasms beyond the dining-room door. The loud foolish screaming of the maid, the answering chorus of wondering ejaculations from the kitchen region, the scuttering footsteps and hurried embassies for outside help, and then, after a lull, the scared sobbings and the shuffling tread of those who bore a heavy burden into the house.

``Whoever will break it to the poor child? I couldn't for the life of me!'' exclaimed a shrill voice. And while they debated the matter among themselves, Conradin made himself another piece of toast.

-

©2025 MarcoFintina.com